In my last post, Halting the Negative Feedback Loop of Poverty: Early Intervention is the Key I looked at the evidence from two quality studies of preschool intervention programs that substantiated a capacity to counteract the impairing impact of growing up in economic deprivation. Both studies, Perry Preschool Program and the Abecedarian Project demonstrated positive long-term benefits with regard to numerous important social and cognitive skills. In this post I shall discuss some interesting issues and concepts that underlie the gains made at Perry and Abecedarian, including fade-out, grit, and positive and negative feedback loops.

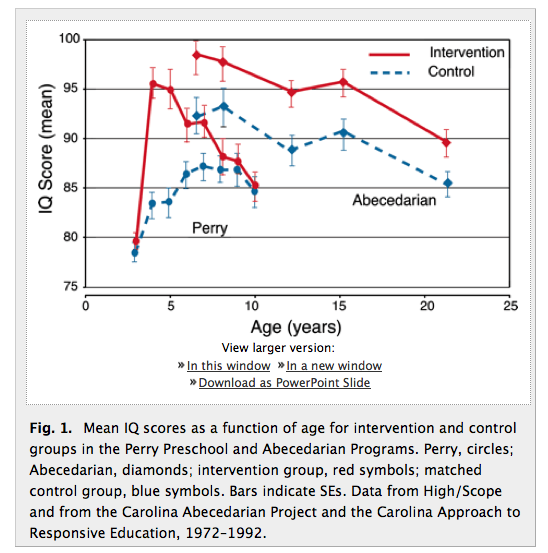

The issue of fade-out, and its implications, are very important. In both the Perry and Abecedarian Programs there were substantial positive outcomes with regard to immediate IQ and other cognitive scores. Once the children entered typical school age programs, some of their gains, particularly their IQ (which had a 10-15 point boost during treatment) faded away. This fade-out was strikingly true for the Perry Preschool Program but not so for the Abecedarian Project, which had a substantially more intensive program, involving both longer school days and more school days per year. See Figure 1 below.

Despite this apparent fade-out, when the recipients of this specialized programing where assessed decades later, they did much better than non-recipients on relative life issues such as high school graduation, four-year college attendance, and home ownership. These results are encouraging on the one hand, yet puzzling on the other. Such fade-out renders programs like Head Start vulnerable to those who cherry pick data in order to advance ideologically driven political agendas. Regardless, this does raise some important questions.

- Why do gains in IQ appear to fade-out?

- What skill gains account for the long-term gains made?

Some prominent researchers (e.g., David Barnett) question whether there is actually any true fade-out at all – suggesting that faulty research design and attrition may better explain these results. Regardless, IQ is not the sole variable at play here – if anything, this data highlights the questionable validity of the IQ construct itself, relative to important life skills. If improved IQ is not the variable that results in improved social outcomes we need to understand what happens to these children as a result of the programming they receive. One likely hypothesis has been proffered to explain these data:

“…the intervention programs may have induced greater powers of self-regulation and self-control in the children, and … these enhanced executive skills may have manifested themselves in greater academic achievement much later in life.” (Raizada & Kishiyama, 2010).

Evidence has been substantiated for this hypothesis by Duckworth et al., (2005, 2007, 2009) who demonstrated that self discipline and perseverance or “grit” is more predictive of academic performance than is IQ and other conventional measures of cognitive ability (Raizada & Kishiyama, 2010). It appears that enhancing one’s grit has the effect of triggering long-term capabilities that are self-reinforcing. Improved self-control and attentiveness fosters achievement that ultimately feeds-back in a positive way making traditional school more rewarding and thus promoting even more intellectual growth (Raizada & Kishiyama, 2010). Poor children, without intervention, on the other hand, appear less able to focus, attend, and sustain effort on learning and thus enter a negative feedback loop of struggle, failure, and academic disenchantment.

The bottom line is that success begets success and failure begets failure. Stanovich (1986) offered an analogous explanation for reading proficiency: “…learning to read can produce precisely such effects: the better a child can read, the more likely they are to seek out and find new reading material, thereby improving their reading ability still further.” (Raizada & Kishiyama, 2010).

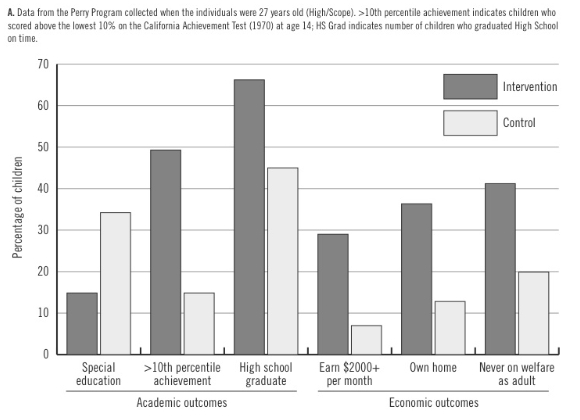

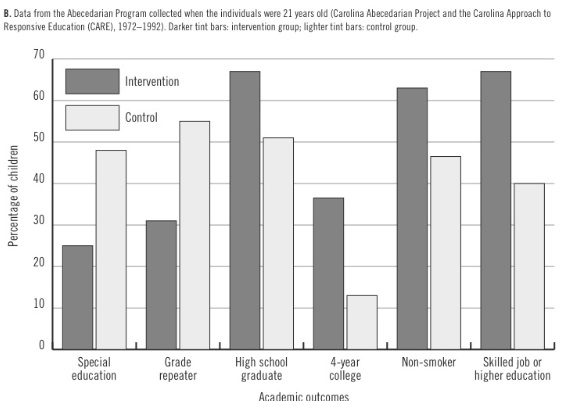

Both the Perry Preschool and Abecedarian Programs have impressive long-term outcome data. See figures 2 & 3 below for a summary of those data.

The efficacy of each program has spawned other programs such as Knowledge is Power Program and the Harlem’s Children’s Zone. Both of these intensive programs lack randomized assignment to treatment and non-treatment (control) groups. As a result, it is difficult to make any claims about their treatment impact on important cognitive and social skills. Given what we learned from the Perry and Abecedarian Programs, I have to wonder whether it would be ethical to withhold such treatment from those children randomly assigned to the control group. It now seems to me, that we absolutely have an ethical obligation to short circuit the negative feedback loop of poverty and put into place universally accessible programs that diminish and/or eradicate poverty’s crippling life long impact.

We all pay a heavy price for poverty, but no one pays a greater cost than those children, who have been thrust into their circumstances, with little hope of rising out of poverty unless we join together to give them a fair shot at economic and social equality.

Yes, such programs cost money, but the long term economic costs of the status-quo are much greater. Pay me now and build positive contributors to society, or pay me later and pay greater costs for special education, prisons, medicaid, and public assistance. It certainly pays to step back from ideology and look at the real costs – both in terms of human lives and in terms of dollars and cents. It makes no sense to continually blame the victims here. Early intervention is good fiscal policy and it is the right thing to do. It just makes sense!

NOTE: In a future post I will look at the evidence put forward by cognitive neuroscience for such programs. Also see The Effects of Low SES on Brain Development for further evidence of the negative impact low SES has on children.

References:

Knudsen, E. I., Heckman, J. J., Cameron, J. L., and Shonkoff, J. P. (2006). Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. v. 103, n. 27. 10155-10162.

Raizada, R. D. S., and Kishiyama, M. M. (2010). Effects of socioeconomic status on brain development, and how cognitive neuroscience may contribute to leveling the playing field. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. v. 4 article 3.

Pingback:The Economic, Neurobiological, and Behavioral Implications of Poverty. - How Do You Think?

Pingback:2013 – A Year in Review: How Do You Think? - How Do You Think?