We humans like to think of ourselves as strong and dominant forces. Why shouldn’t we? After all, we have conquered many of our natural foes and reign supreme as rational and commanding masters of our destiny. That is what we like to think. But this may be an illusion because as it turns out, we share our bodies with an unimaginably vast array of organisms that seem to play a substantial role in our well-being.

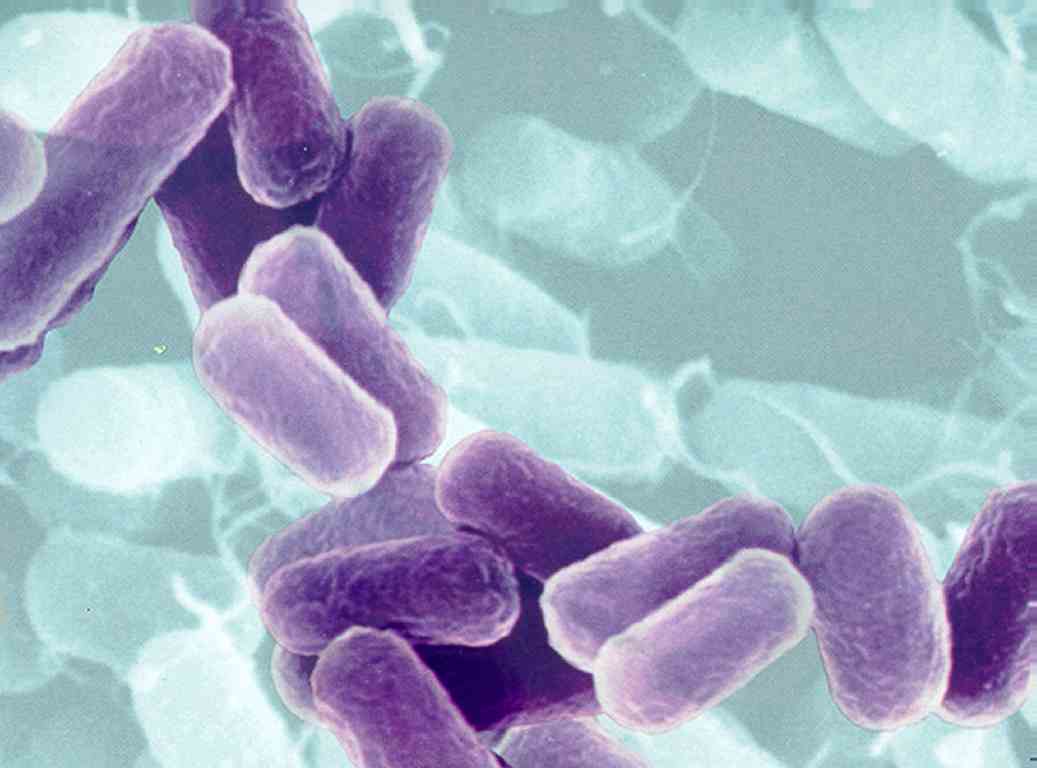

In and on your body, there are ten microorganisms for every single human cell. They are invisible to the naked eye – microscopic actually. For the most part they are bacteria, but also protozoans, viruses, and fungi. This collection of organisms is referred to as the microbiome and it accounts for about three pounds of your total body weight: about the same weight as your brain. In all, there are an estimated 100 trillion individuals thriving on your skin, in your mouth, in your gut, and in your respiratory system, among other places. And it is estimated that there are one to two thousand different species making up this community.(2)

Since wide spread acceptance of the Germ Theory, in the late nineteenth century, we have considered bacteria as the enemy. These organisms are germs after all, and germs make us sick. This is accurate in many ways: acceptance and application of the germ theory vastly extended the human life expectancy (from 30 years in the Dark Ages to 60 years in the 1930s). Other advances have since increased that expectancy to about 80 years.

But, as we are increasingly becoming aware, this microbiome plays a crucial role in our ability to live in the first place. There are “good” and “bad” microbes. But this dichotomy is not so black and white. Some good microbes turn problematic only if they get in the wrong place (e.g., sepsis and peritonitis). But what we must accept is that we would not survive without the good ones. We are just beginning to learn of the extent to which they control our health and even our moods.

For example, some of our nutritive staples would be of very limited value if it wasn’t for Baceroides thetaiotaomicron. This microbe in our stomach has the job of breaking down complex carbohydrates found in foods such as oranges, apples, potatoes, and wheat germ. Without this microbe we simply do not have the capability to digest such carbohydrates.(1) And this is just the tip of the proverbial iceberg.

The “beneficial” bacteria in our guts are clearly very important. They compete with the harmful bacteria, they help us digest our food, and they help our bodies produce vitamins that we could not synthesize on our own.(3) Surprisingly, these microbes may play a significant role in our mood. A recent study looking at the bacteria lacto bacillus, fed to mice, resulted in a significant release of the neurotransmitter gaba which is known to have a calming affect. When this relationship was tested in humans we discovered a relationship between such gut bacteria and calmness to a therapeutic level consistent with the efficacy of anti-anxiety pharmaceuticals.(2) This alone is amazing.

But wait, there’s more. Take for example Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) whose job seems to be regulating acid levels in the stomach. It acts much like a thermostat by producing proteins that communicate with our cells signaling the need to tone down acid production. Sometimes things go wrong and these proteins actually provoke gastric ulcers. This discovery resulted in an all out war on H pylori through the use of antibiotics. Two to three generations ago more than 80% of Americans hosted this bacteria. Now, since the discovery of the connection with gastric ulcers, less than 6% of American school children test positive for it.(1) This is a good thing! Right?

Perhaps not. As we have recently come to discover, H pylori plays an important role in our experience of hunger. Our stomach produces two hormones that regulate food intake. Ghrelin (the hunger hormone), tells your brain that you need food. Leptin, the second hormone, signals the fact that your stomach is full. Ghrelin is ramped up when you have not eaten for a while. Exercise also seems to boost Ghrelin levels. Eating food diminishes Ghrelin levels. Studies have shown that H pylori significantly regulates Ghrelin levels and that without it your Ghrelin levels may be unmediated thus leading to a greater appetite and excessive caloric intake.(1) Sound like a familiar crisis?

The long and the short of this latter example is that we really do not understand the down stream consequences of our widespread use of antibiotics. Obesity may be one of those consequences. When we take antibiotics, they do not specifically target the bad bacteria, they affect the good bacteria as well. Its not just medical antibiotics that cause problems – we have increasingly created a hygienic environment that is hostile to our microbiome. We are increasingly isolating ourselves from exposure to good and bad bacteria, and some suggest that this is just making us sicker. See the Hygiene Hypothesis.

We have co-evolved with our microbiome and as such have developed an “immune system that depends on the constant intervention of beneficial bacteria... [and] over the eons the immune system has evolved numerous checks and balances that generally prevent it from becoming either too aggressive (and attacking it’s own tissue) or too lax (and failing to recognize dangerous pathogens).”(1) Bacteroides fragilis (B fragilis) for example has been found to have a profoundly important and positive impact on the immune system by keeping it in balance through “boosting it’s anti-inflammatory arm.” Auto immune diseases such as Chrones Disease, Type 1 Diabetes, and Multiple Sclerosis have increased recently by a factor of 7-8. Concurrently we have changed our relationship with the microbiome.(1) This relationship is not definitively established but it clearly merits more research.

Gaining a better understanding of the microbiome is imperative, and is, I dare say, the future of medicine. We humans are big and strong, but we can be taken down by single celled organisms. And if we are not careful stewards of our partners in life, these meek organisms may destroy us. It is certain that they will live on well beyond our days. Perhaps they shall reclaim the biotic world they created.

Author’s Note: This article was written in part as a summary of (1) Jennifer Ackerman’s article The Ultimate Social Network in Scientific American (June 2012). Information was also drawn from (2) a Radio Lab podcast titled GUTS from April of 2012 and (3) a story on NPR by Allison Aubrey called Thriving Gut Bacteria Linked to Good Health in July of 2012.

For more interesting research on this topic see a recent article in Scientific American titled Antibiotics Linked to Weight Gain that noted that “Changes in the gut microbiome from low-dose antibiotics caused mice to gain weight. Similar alterations in humans taking antibiotics, especially children, might be adding to the obesity epidemic.” at http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=antibiotics-linked-weight-gain-mice&WT.mc_id=SA_DD_20120828

“The human gut is an amazing piece of work. Often referred to as the “second brain,” it is the only organ to boast its own independent nervous system, an intricate network of 100 million neurons embedded in the gut wall. So sophisticated is this neural network that the gut continues to function even when the primary neural conduit between it and the brain, the vagus nerve, is severed.” From a great article at the American Psychological Association’s Monitor on Psychology.

Even more powerful implications of the Microbiome from NPR’s Science Friday http://www.npr.org/2012/09/14/161156793/microbes-benefit-more-than-just-the-gut

something about its fundament iraomtpnce in higher life forms. The theory about how the functional gene got into this unique cyanobacterium is that the bug acquired the gene from a broken intestinal gut cell where the bacterium resided inside a marine invertebrate. This seems possible if all living animals have more bacteria in their bodies than their own number of cells (the NYTimes article linked above). So bacteria can sometimes (though rarely) further evolve from humans or other animals by acquiring their genes. For this to have been discovered, the cyanobacterium must have gained a growth advantage in its ecological niche by acquiring an actin gene; otherwise it would never have been found and would have eventually disappeared. Its survival is due to natural selection (Darwin).

Pingback:2012 – A Year in Review: How Do You Think? - How Do You Think?

Here is yet another article with predictions about what we will learn, in time, about our relationship with the microbiome – at Scientific American: http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/2013/03/19/ten-predictions-on-the-future-of-your-microbial-health/?WT_mc_id=SA_DD_20130319

Another article with microbiome and health implications at Scientific American: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=red-meat-clogs-arteries-bacteria&WT.mc_id=SA_DD_20130408

North Carolina State University biologist Rob Dunn and colleagues surveyed people’s pillow cases, refrigerators, toilet seats, TV screens and other household spots, to learn about the microbes that dwell in our homes. Like in the greater ecosystem – the greater the biodiversity the better off we tend to be. See Science Friday post at http://www.npr.org/2013/05/24/186450897/having-a-dog-may-mean-having-extra-microbes

The microbiome also includes fungi. Here is an interesting podcast from the journal Nature on this subset on those tiny organisms that live in us and on us. Play Fungal Friends at: http://www.nature.com/nature/podcast/index-2013-05-23.html

FROM SCIENCE FRIDAY “In a new study, researchers were able to make mice lean or obese by altering their gut bacteria. Jeffrey Gordon, an author of the study, discusses how the interaction between diet and the microbial community in our gut influences our health.” http://www.sciencefriday.com/segment/09/06/2013/do-your-gut-bacteria-influence-your-metabolism.html

Q: Can changing your diet alter your microbiome?

A: It’s complicated – a cursory review at NPR http://www.npr.org/blogs/thesalt/2013/11/08/243929866/can-we-eat-our-way-to-a-healthier-microbiome-its-complicated

How Probiotics May Save Your Life by Rob Dunn

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/2011/07/18/how-probiotics-may-save-your-life/

Gut Bacteria Might Guide The Workings Of Our Minds by Rob Stein:

http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2013/11/18/244526773/gut-bacteria-might-guide-the-workings-of-our-minds

A great image in this short piece by Carl Zimmer that captures the breadth of the microbiome in and on you. Check it out at: http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/loom/2010/10/03/time-for-a-da-vinci-upgrade-the-microbiome-image-of-the-day/

By the way – he shared it – but it was published in a paper at http://www.sciencemag.org/content/326/5960/1694.abstract

Gut Bacteria May Exacerbate Depression from Scientific American: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=gut-bacteria-may-exacerbate-depress

Proof of concept – altering diet alters the microbiome – quickly and substantially: From NPR – a review of a paper published in Nature. http://www.npr.org/blogs/thesalt/2013/12/10/250007042/chowing-down-on-meat-and-dairy-alters-gut-bacteria-a-lot-and-quickly?utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=20131215&utm_source=mostemailed

Proof of concept – Consumption of Fermented Milk Product With Probiotic Modulates Brain Activity. From the journal: Gastroenterology

Volume 144, Issue 7 , Pages 1394-1401.e4, June 2013

http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085%2813%2900292-8/abstract

Can parasites prevent autoimmune diabetes? Posted by Human Food Project on 15 Jan 2013 in Human Food Project

http://humanfoodproject.com/can-parasites-prevent-autoimmune-diabetes/