Nobody likes a cheater. Such acts may stir deep feelings of loathing that erode trust and have ruinous consequences with regard to reputation and relationship. It’s one of those things that is hard to overcome. I’m not just talking about infidelity here. I’m referring to a broader type that does include infidelity, but also includes things like pilfering, speeding, lying about one’s age, and other forms of dishonesty that benefit you at a cost to someone else. Irrespective of the potential social costs, most people, given the opportunity, with little threat of detection, will and DO cheat. Be honest with yourself here. This shouldn’t be surprising. What is surprising is the fact that altruism, or selflessness, the behavioral opposite of cheating, exists at all.

By virtue of the fact that human beings are the product of millions of years of evolution by means of natural selection, we are imbued with a selfishness that is hard to deny. As distasteful as this may be, it is nonetheless true. We are compelled by our selfish genes to survive, thrive, and replicate. Within this context, cheating and selfishness make perfect sense and altruism makes little. Yet we do exhibit altruism. Why is this? Steven Pinker wrote in How the Mind Works (1997, p 337):

Natural selection does not select public-mindedness; a selfish mutant would quickly out reproduce its altruistic competitors. Any selfless behavior in the natural world needs a special explanation. One explanation is reciprocation: a creature can extend help in return for help expected in the future. But favor-trading is always vulnerable to cheaters. For it to have evolved, it must be accompanied by a cognitive apparatus that remembers who has taken and ensures that they give in return. The evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers had predicted that humans, the most conspicuous altruists in the animal kingdom, should have evolved a hypertrophied cheater-detection algorithm.

And indeed we have – this cognitive algorithm drives the emotional response we have toward cheaters. Human beings are one of the few species that engage in altruism outside of their kin. This is referred to as Reciprocal Altruism and clear links have been established between the demands of this type of social exchange and the origins of many human emotions (e.g., liking, anger, gratitude, sympathy, and guilt). Pinker (1997) notes that “Collectively they make up a large part of the moral sense.” We are inclined to engage in reciprocal altruism because we have the cognitive capacity to compute cost benefit analyses and the emotional capacity to respond in ways to encourage gains and discourage losses. We have to be able to remember favors given and received and we must effectively calibrate reciprocation. It is a delicate and intricate dance that if kept in balance does result in both individual and group benefits.

When benefits or favors are traded, both parties profit as long as the value of what they receive is greater than the value of what they give up. Because most favors are not exchanged at the same time and they likely vary in degree of effort and value, a calculus is needed to keep the exchange in reciprocal balance. This balance can tip in either direction and people “remember past treacheries or good turns and play accordingly. They can feel sympathetic and extend good will, feel aggrieved and seek revenge, feel grateful and return a favor, or feel remorseful and make amends.” (Pinker, 1997 p. 503).

It is important to note that there is a different calculus, a more flexible and enduring one that plays out in friendships and kin based, as well as intimate relationships. “Tit-for-tat does not cement a friendship; it strains it. Nothing can be more awkward for good friends than a business transaction between them, like the sale of a car. The same is true for one’s best friend in life, a spouse. The couples who keep close track of what each other has done for the other are the couples who are the least happy.” (Pinker, 1997 p. 507). Healthy close relationships come with a feeling of indebtedness and spontaneous pleasure associated with contribution instead of anticipation of in-kind repayment. This is true to a point however, and if one person takes too much, without giving back, the relationship is likely doomed. In such healthy relationships, there tends to be compassionate and enduring love, free of ledgers, time cards, and cash register receipts.

So, we are hyper-vigilant cheater detectors, and our scrutiny of others’ cheating behavior varies based on a number of variables. Certainly kinship and friendship play a part in our perception. But in addition to what we understand about reciprocal altruism and cheating, we also know that our cheater detectors tend to be finely focused on people who are different from us. Those outside our identified social groups (tribal moral communities) are scrutinized much more closely than those inside our circles – and they are examined with much more resolution than we direct toward our own conduct and toward those in the in-group.

This inclination is a byproduct of the universal and innate tendencies to be much more forgiving toward one’s own mistakes and more judgmental towards others’ transgressions. This is the self-serving bias. We also have a tendency to see exactly what we expect to see and miss or ignore things that don’t fit within our expectations. These tendencies are explained by our inclinations toward confirmation bias and inattentional blindness. Finally, there is the fundamental attribution error which leads us to blame others’ transgression on their internal personal attributes while we ignore important and contributing external environmental circumstances.

That is a lot to take in, but suffice it to say that we are much more likely to give ourselves and those similar to us, a break when it comes to cheating. We are much less forgiving toward outsiders, particularly those that seem to hold different values, norms, or customs. This is even true within a society where there is, to a substantial extent, social cohesion; but, where differences exist with regard to beliefs or ideologies. These truths are self evident – just look at the rancor between Liberals and Conservatives in the United States. But it also helps explain the racial and ethnic tensions within and across this country toward Hispanics, African Americans, Muslims, and particularly, the poor.

Currently, much blame for this country’s financial woes has been heaped onto the poor due to “entitlement spending.” These recipients of social safety net spending are often defined as cheaters and freeloaders. There is no doubt that there is, and shall forever be, a small contingent of citizens who are completely comfortable with getting a free ride. It would be foolish to argue otherwise. This is a legitimate problem.

On the other hand, I suggest that we must be willing to acknowledge the prevalence of cheating across the economic spectrum and refocus our microscope on the costs of cheating by corporations, white collar criminals, and those whom we tend to give a pass because they are similar to us. In my previous article, Crime & Punishment and Entitlements: A Deeper Perspective, I discussed the egregious costs of our prejudicial criminal justice system and the entitlement mentality rampant in corporations and those at the upper end of the economic spectrum. I submitted that article with the intent of opening eyes to the wider hypocrisy that pervades this country and the erroneously sharpened focus on a small fraction of our fellow “freeloading” countrymen. If you believe that the infamous 47% of Americans are truly freeloaders, I suggest that you take an objective look at the data from that group (from FactCheck.org):

- 22 percent [or around 47% of the 47%] receive senior tax benefits — the extra standard deduction for seniors, the exclusion of a portion of Social Security benefits, and the credit for seniors. Most of them are older people on Social Security whose adjusted gross income is less than $25,000.

- 15.2 percent [or 32% of the 47%] receive tax credits for children and the working poor. That includes the child tax credit and the earned income tax credit. The child tax credit was enacted under Democratic President Bill Clinton, but it doubled under Republican President George W. Bush. The earned income tax credit was enacted under Republican President Gerald Ford, and was expanded under presidents of both parties. Republican President Ronald Reagan once praised it as “one of the best antipoverty programs this country’s ever seen.” As a result of various tax expenditures, about two thirds of households with children making between $40,000 and $50,000 owed no federal income taxes.

- The rest [21% of the 47%] ended up owing no federal income tax due to various tax expenditures such as education credits, itemized deductions or reduced rates on capital gains and dividends. Most of this group are in the middle to upper income brackets. In fact, the TPC [Tax Policy Center] estimates there are about 7,000 families and individuals who earn $1 million a year or more and still pay no federal income tax.

According to the US Federal Budget, in 2012 we spent about $187 billion on traditional welfare programs (e.g., food and housing supplementation and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families), accounting for 5% of the total $3.7 trillion budget. An additional $333 billion (or 8.9% of the budget) was spent on Medicaid (healthcare for the poor and disabled). In total about fourteen cents (14¢) of every tax dollar you pay goes to the poor.

For relative comparison, in 2012, $925.2 billion (or 25% of the 2012 budget or 25¢ of every tax dollar) went to defense, $805.6 billion (21.6% or about 22¢ of every tax dollar) went out in Social Security income for seniors citizens, $492.3 billion (13.2% or 13¢ of each tax dollar) went to Medicare (healthcare for our seniors), and $121.1 billion (3.2% or 3¢) went toward education. The remaining expenses include unemployment, building roads and bridges, government operating costs, public safety, government supported research, interest payments, and so on.

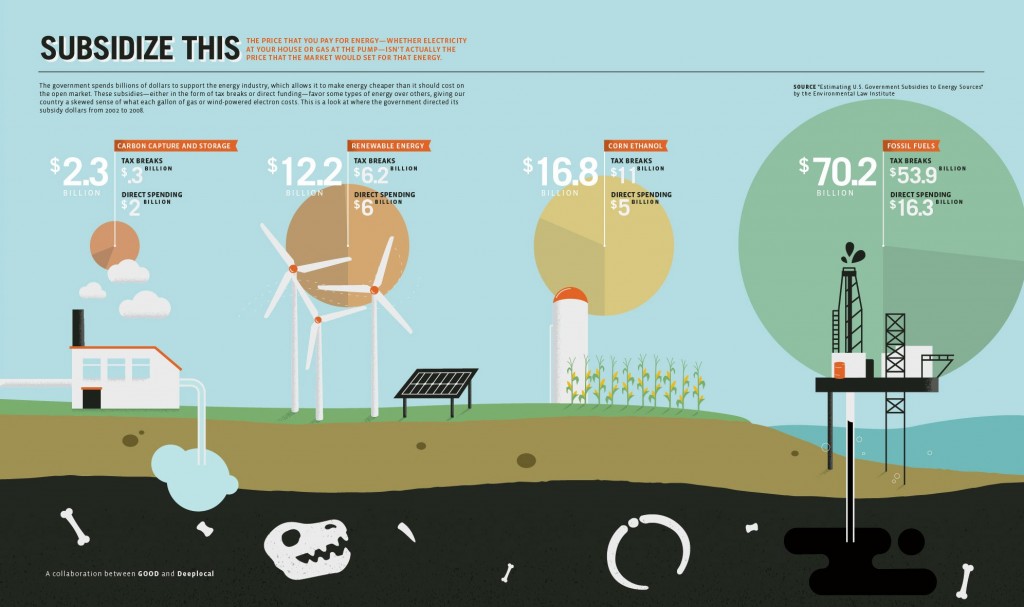

For further comparison, according to a report from the Conservative think tank The Cato Institute, in 2006 $92 billion (3.5% of the 2006 budget or about 4¢ of every tax dollar) went to corporate subsidies. This “Corporate Welfare” was defined by Cato as “any federal spending program that provides payments or unique benefits and advantages to specific companies or industries.” Cato indicated that corporations such as “Boeing, Xerox, IBM, Motorola, Dow Chemical, General Electric and others” were recipients of your tax dollars and Cato further noted that such companies “have received millions in taxpayer-funded benefits through programs like the Advanced Technology Program and the Export-Import Bank.” Additionally, it should be noted, that between 2002 and 2008, tax breaks totaling $53.9 billion and $16.3 billion in direct spending for a total of $70.2 billion were directed to companies in the fossil fuel industries (e.g, Exxon-Mobile, Shell, Chevron).

Clearly that 14¢ of every tax dollar has triggered much contempt in a significant proportion of our population. Many outspoken Conservative and Tea Party folks heavily focus on the this portion of the budget and the “entitled” individuals who allegedly, willingly and lazily, live off your hard earned money. We must acknowledge that these angered individuals are endowed with this tendency as a natural result of our altruistic tendencies and our subsequent finely tuned cheater detection neural software. And I submit, that this software has been hijacked or perhaps even hacked by the those whose gains are ignored as long as you focus your anger at the poor. It serves the very specific financial and security interests of the wealthy when Americans direct such anger toward those at the bottom of the spectrum rather than those at the top. Next time you come across an economic “freeloader” I challenge you to really think about the cheating that occurs across the spectrum, and ask yourself whether there is a chance that your anger has been manipulated and perhaps even misdirected. Coming together on this issue will likely result in more targeted and effectual reforms that will benefit us all. The splinters that currently exist keep our collective eyes off the ball. The result is an ever widening disparity between the wealthiest 1% and the rest of us.

Pingback:Who Cheats More: The Rich or the Poor? - How Do You Think?

Pingback:2013 – A Year in Review: How Do You Think? - How Do You Think?