The United States is the richest nation in the world, nevertheless, 2007 Census data indicates that 17.4% of our children live in poverty. That translates into 1 in 6 kids living in a state of economic deprivation. These huge numbers of our most vulnerable are growing up in circumstances completely beyond their control; yet, they, and ultimately all of us, pay for the lifelong consequences of this state of affairs.

A large and growing body of research has been devoted to understanding the real world developmental implications of such deprivation. It is widely believed that poverty is bad for kids. Genetic and cognitive neuroscience seems to be substantiating that this relationship does in fact impede the development of important life-long social and cognitive skills. For example: children who grow up in poverty evidence diminished: (a) phonemic awareness, (b) vocabulary, (c) verbal math skills, (d) control over attention to task, (e) working memory, (f) executive functioning, and (g) incidental learning capabilities (Knudsen, et al., 2006, Raizada and Kishiyama, 2010). Diminished capacity in any of these areas degrades one’s ability to make the best of learning opportunities provided.

Many folks comfortably blame those in poverty for their circumstances, suggesting that genetic inferiority, personal character traits, or irresponsible choices land poor people in their circumstances. Some comfortably point at the “culture of poverty” as the culprit while believing that their own superior work ethic and drive for success solely differentiates them from their poor brethren. Despite a plethora of data indicating that this thinking essentially blames the victim, it persists.

Evidence suggests that genes may in fact play a part in this affluence disparity, but, it is becoming increasingly clear that environment plays a crucial role in how those genes are expressed. Specifically, “some genes are turned on or off, or can have their expression levels adjusted by experience.” (Knudsen, et al, 2006). Clearly environment impedes the development of the important social and cognitive skills described above and thus creates a negative feedback loop that sustains folks in perpetual poverty. With this knowledge in hand, it is becoming ethically and fiscally necessary to understand the mechanism through which deprivation actually affects brain development.

Cognitive neuroscience, through brain imaging studies, is increasingly providing an understanding of this mechanism. More to come on this in subsequent posts. It is equally important to understand whether there are intervention strategies that can remediate or limit the implications of such deprivation.

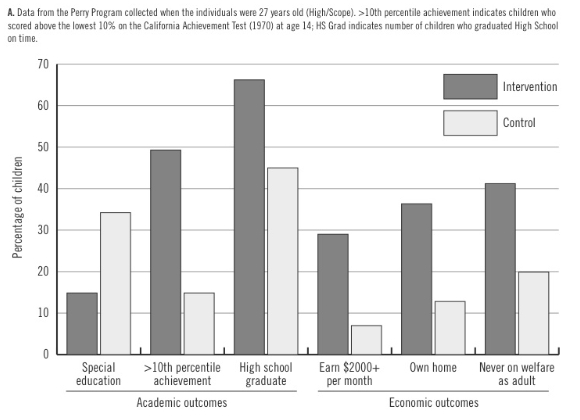

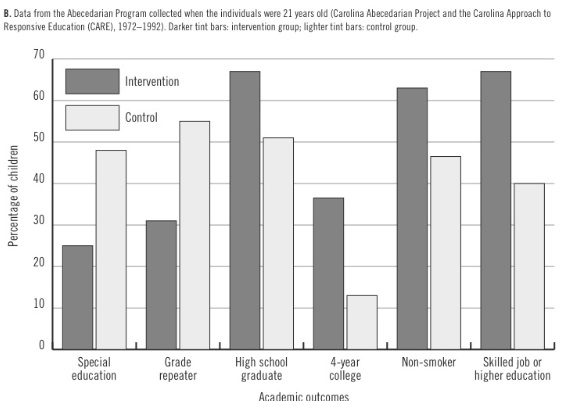

There are two robust and reasonably well designed studies of Early Intervention Programs for disadvantaged children that do appear to remediate, to a substantial degree, the negative impact of growing up in poverty. These include the Perry Preschool Program and the Abecedarian Program. Each of these programs set out to see if intervention has any hope of blocking this negative feedback. Each study used randomized child assignment and long-term follow up to evaluate the implications of the provided interventions on social behavior and cognitive development. The summary below is from Knudsen, et al, 2006.

The Perry Program was an intensive preschool program that was administered to 64 disadvantaged, black children in Ypsilanti, MI, between 1962 and 1967. The treatment consisted of a daily 2.5-h classroom session on weekday mornings and a weekly 90-min home visit by the teacher on weekday afternoons. The length of each preschool year was 30 weeks. The control and treatment groups have been followed through age 40. The Abecedarian Program involved 111 disadvantaged children, born between 1972 and 1977, whose families scored high on a risk index. The mean age at entry was 4.4 months. The program was a year-round, full-day intervention that continued through age 8. The children were followed up until age 21, and the project is ongoing.

In both the Perry and Abecedarian Programs, there was a consistent pattern of successful outcomes for treatment group members compared with control group members. For the Perry Program, an initial increase in IQ disappeared gradually over 4 years after the intervention, as has been observed in other studies. However, in the more intense Abecedarian Program, which intervened earlier (starting at age 4 months) and lasted longer (until age 8), the gain in IQ persisted into adulthood (21 years old). This early and persistent increase in IQ is important because IQ is a strong predictor of socioeconomic success.

See the figures below (Knudsen, et al, 2006) for the data on these programs.

As can be seen above, the positive effects of these interventions were also documented for a wide range of social behaviors. Again from Knudsen, et al, 2006:

At the oldest ages tested (Perry, 40 yrs; Abecedarian, 21 yrs), individuals scored higher on achievement tests, reached higher levels of education, required less special education, earned higher wages, were more likely to own a home, and were less likely to go on welfare or be incarcerated than individuals from the control groups. Many studies have shown that these aspects of behavior translate directly or indirectly into high economic return. An estimated rate of return (the return per dollar of cost) to the Perry Program is in excess of 17%. This high rate of return is much higher than standard returns on stock market equity and suggests that society at large can benefit substantially from these kinds of interventions.

Clearly, poverty inherently impedes individuals’ potential and renders them less able to contribute to society in a meaningful way. There is ample reason to consider social programs that have proven capacity to limit the negative and disabling consequences of growing up poor. All of us pay a price for poverty whether it be through the criminal justice system, income assistance programs, special education programs, or publicly assisted medical care. Doesn’t it make sense to invest proactively in our children so that we don’t have to respond in a reactive manner after the damage has already been done?

It was once said that “every society is judged by how it treats the least fortunate amongst them.” I believe that this is true. Even if you don’t believe this to be true, from an economic perspective, it just makes good sense to halt this negative feedback loop – and early intensive intervention is the key to success. This will benefit all of us.

References:

Knudsen, E. I., Heckman, J. J., Cameron, J. L., and Shonkoff, J. P. (2006). Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. v. 103, n. 27. 10155-10162.

Raizada, R. D. S., and Kishiyama, M. M. (2010). Effects of socioeconomic status on brain development, and how cognitive neuroscience may contribute to leveling the playing field. Fontiers in Human Neuroscience. v. 4 article 3.

Pingback:Poverty Preventing Preschool Programs: Fade-Out, Grit, and the Rich get Richer – How Do You Think?

Pingback:The Economic, Neurobiological, and Behavioral Implications of Poverty. – How Do You Think?