Citizens of the United States are endowed with certain unalienable rights: one of which is the right to pursue happiness. Governments generally need to attend to the common level of happiness of its citizens in order to sustain power. As evidenced by the Arab Spring, unhappy people have the capability to overthrow ineffectual governments. As it turns out, the way politicians and economists presume to measure happiness is through a statistical measure called the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Let’s take a closer look at GDP and ponder the questions as to whether it is, in fact, an appropriate measure with regard to overall happiness.

Following World War II, a metric called the Gross National Product (GNP) was adopted as the key indicator of a nation’s economic growth. Eventually GDP replaced GNP and it acquired broader meaning as a proxy of individual well-being (happiness). But what does GDP really measure? GDP as defined by InvestorWords.com is:

The total market value of all final goods and services produced in a country in a given year, equal to total consumer investment and government spending, plus the value of exports, minus the value of imports.

GDP is the measure we look at to determine whether our economy is growing, in recession, or in depression. This makes sense. But the deeper fundamental belief is that GDP equates to personal wealth, and that the more personal wealth individuals posses, the happier they will be. Our economy grows when people have money and spend it. The bottom line assumption here is that money buys happiness.

Since developed nations have strategically attended to this measure, GDP has skyrocketed. Concurrently, there have been unequivocal rises in living standards and wealth. The United States has done relatively well in this regard. But you might be surprised to know that according to a CIA website, the US ranks 12th in the world on a measure of GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) behind countries like Qatar, Luxembourg, Norway, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Brunei.

In poor nations where GDP is very low, quality of life and subjective measures of happiness are indeed low. As GDP increases, there is a correlated increase in both quality of life and happiness. But that relationship holds up, only to a certain point, and then it falls apart. For example, in developed Western Democracies such as the United States, UK, and Germany, since the 1970’s, GDP has grown, but on a variety of more direct measures, the happiness of its citizens has stagnated or declined. See the chart below from James Gustave Speth’s book The Bridge at the Edge of the World.

As it turns out, when a nation’s GDP rises above $10,000.00 per capita there is no relationship between GDP and happiness. For a reference point, in the United States our GDP per capita rose above this $10k point in the 1960s and is currently around $50k per capita. The reality is that despite a five-fold increase in personal wealth, people as a whole, are no more happy today than they were in the 1970s. This suggests a fundamental flaw in the thinking of our policy makers.

I am not alone, nor am I first to point out the problem with assuming that GDP equates to citizen happiness. James Gustave Speth, provides a ground shaking critique of our current political, economic, and environmental policies in his 2008 book The Bridge at the Edge of the World. This GDP-Happiness issue is a prominent theme in his book and he explores what actually accounts for happiness. What follows is a summary of Speth’s discussion of this topic.

Research suggests that there are a number of important factors associated with individual happiness. What is interesting is that the major factors are relativistic, innately internal, as well as social and interpersonal. Yes, below a certain point, when people are impoverished and struggling to survive, happiness is indeed tied to GDP. But above that $10K GDP per capita line, these other human factors play a major role.

Let us start with perhaps the most powerful factor associated with happiness, our genes. It is estimated that about one-half of the variability in happiness is accounted for by our genetic composition. One’s happiness is much like one’s personality, to a large extent it is written in our DNA. Some people are just congenitally happier than others. Some are chronic malcontents no matter what the circumstances provide. Such proclivities are difficult to override. But the remaining 50% of variance in happiness does seem to be rooted in variables that we can influence.

One’s relative prosperity is a clear variable. There is an inverse relationship between happiness and one’s neighbors’ wealth. If you are relatively well-off compared to those around you, you are likely to experience more happiness. If however, you are surrounded by people doing much better than you (financially), you are likely to experience discontent. It is more about relative position rather than absolute income. And as everyone’s income rises, one’s relative position generally remains stable. So more money does not necessarily equate to more happiness.

Yet another innately human factor that plays out in this happiness paradox is our incredible tendency to quickly habituate to our income and the associated material possessions that it affords. We seem to have a happiness set point. There may be an initial bump in happiness associated with a raise, a bigger better car, or a new house; however, we tend to return to that set point of happiness pretty quickly. We habituate to the higher living standards and quickly take for granted what we have. We then get a relative look at what’s bigger and better and begin longing for those things. This is the hedonic treadmill.

Happiness is to a large extent associated with seven factors:

- Family relationships

- One’s relative financial situation

- The meaningfulness of one’s work

- Ties to one’s community and friends

- Health

- Personal freedom

- Personal values

Speth notes that “except for health and income, they are all concerned with the quality of our relationships.” We clearly know that people need deeply connected and meaningful social relationships. Yet we are living increasingly disconnected and transient lifestyles where we relentlessly pursue increasing affluence all the while putting distance between us and what we truly need to be happy. We are on that hedonic treadmill convinced that happiness comes from material possessions, all the while neglecting the social bonds that truly fulfill us.

Obviously, GDP misses something with regard to happiness. Speth quotes Psychologist David Meyers who wrote about this American Paradox. At the beginning of the twenty-first century he observed that Americans found themselves:

“with big houses and broken homes, high incomes and low morale, secured rights and diminished civility. We were excelling at making a living but too often failing at making a life. We celebrated our prosperity but yearned for purpose. We cherished our freedom but longed for connection. In an age of plenty, we were feeling spiritual hunger. These facts of life lead us to a startling conclusion: Our becoming better off materially has not made us better off psychologically.”

The reality is that there is a great deal of disillusionment in this country (The United States). And we are falling behind in other areas of significant importance. Our healthcare systems ranks 37th in the world with regard to life expectancy. The efforts of our education system finds us loosing touch with the world’s top performers. A 2010 US Department of Education report releasing the 2009 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores indicated that 15-year-old students from the US scored in the average range in reading and science, but below average in math. Out of the 34 countries in the study, the US ranked 14th in reading, 17th in science and 25th in math. The US students ranked far behind the highest scoring countries, including South Korea, Finland, Canada, and Singapore, Hong Kong and Shanghai each in China. Secretary Duncan, at the time of the PISA announcement, said that:

“The hard truth is that other high-performing nations have passed us by during the last two decades…In a highly competitive knowledge economy, maintaining the educational status quo means America’s students are effectively losing ground.”

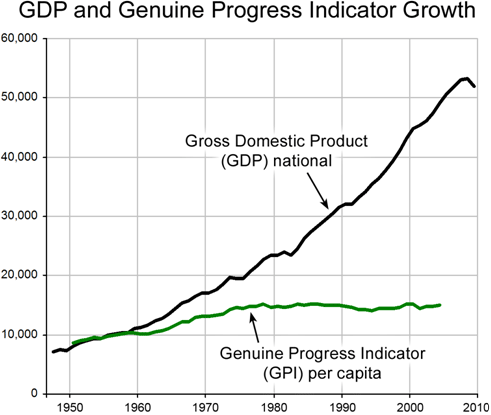

Although GDP is an important economic measure, many economists and some leaders suggest that we should assess well-being more precisely. For example, alternatives include the Genuine Progress Index (GPI) that factors into the equation environmental and social costs associated with economic progress. See the graph below for how we in the US have fared on GPI.

This GPI data suggests that since the early seventies there has been a clear divergence between GDP and the well-being of the citizens of the United States. This GPI line correlates strongly with the relative happiness line over the same time period.

Another effort made with regard to measuring the well-being of the citizens is the Index of Social Health put forward by Marc and Marque-Luisa Miringoff. They combined 16 measures of social well-being (e.g., infant mortality, poverty, child abuse, high school graduation rates, teenage suicide, drug use, alcoholism, unemployment, average weekly wages, etc.) and found that between 1970 and 2005 there has also been a deteriorating social condition in the United States despite exponential growth in GDP.

The New Economics Foundation in Britain has developed the Happy Planet Index (HPI) that essentially measures how well a nation converts finite natural resources into the well-being of its people. The longer and happier people live with sustainable practices the higher the HPI. The United States scores near the bottom of this list. At the top of the list in the Western Developed nations are countries like Malta, Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Iceland, and the Netherlands (due to long happy lives and lower environmental impact). At the bottom across all nations are countries like the US, Qatar, UAE, Kuwait (each as a result of atrocious environmental impact) and Rwanda, Angola, Sudan and Niger (due to significantly shortened life spans).

“Right now,” Speth notes, “the reigning policy orientation and mindset hold that the way to address social needs and achieve better, happier lives is to grow – to expand the economy. Productivity, wages, profits, the stock market, employment, and consumption must all go up. Growth is good. So good that it is worth all the costs. The Ruthless Economy [however] can undermine families, jobs, communities, the environment, a sense of place and continuity, even mental health, [but] in the end, it is said, we’ll somehow be better off. And we measure growth by calculating GDP at the national level and sales and profits at the company level. And we get what we measure.”

All this taken together seems to suggest that we would be better off as a citizenry if we radically re-prioritized our economic, social, and environmental policies with increased focus on factors that more closely align with human well-being. Yet, we continually forge ahead striving unquestionably for economic growth because we believe it will make us better off. Closer scrutiny suggests that we should broaden our thinking in this regard. If we were to focus our energies on GPI and/or HPI, like we have on GDP over the last 50 years, just imagine what we could accomplish.

References:

Central Intelligence Agency. The World Fact Book: GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP).

Guild, G. (2011). We’re Number 37! USA! USA! USA!

Johnson, J. (2010). International Education Rankings Suggest Reform Can Lift U.S. US Department of Education.

Speth, James Gustave. (2008). The Bridge at the Edge of the World. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Pingback:2012 – A Year in Review: How Do You Think? - How Do You Think?

Pingback:2013 – A Year in Review: How Do You Think? - How Do You Think?

I would like to include the two graphs (Average income versus happiness; and GDP versus GPI) from this article in a sustainability book I am writing and self publishing. Each graph will be approximately 2-3/4″ wide, and the proper source cited with the image. I would greatly appreciate permission to use these two images. If you are not the copyright holder, can you please help me contact the correct person? Thank you so much!

Hi Linda,

The average income versus happiness graph is from James Gustave Speth’s book The Bridge at the End of the World . I typically reference my sources, but seem to have missed the reference for the GDP vs GPI graph you mention. There is a reproduction form Venetoulis & Cobb (2004)

The Genuine Progress Indicator

in Speth’s book, but it’s not exactly the same as the one I have in my article. I’ve searched for my source because I want the article to be properly referenced but I’m coming up empty. My apologies to you and all my readers! I will strive to track that image down or change it and reference it properly. Good luck to you on your book – I’d very much like to read it when you publish.

Gerry

Pingback:Is It Time To Rethink the Economics of Happiness? – Berkeley Political Review

Pingback:Local Currencies, Cryptocurrencies and the End of Plutocracy – INDEPENDENT CURRENCIES