There is an Indigo Girls song called Galileo that references a fear of motion (00:01:19 into the song) and suggests that the source of this particular fear is from “some other fool across the ocean years ago [having] crashed his little airplane.” In the song, the means of transmission of this fear is reincarnation, which according to dictionary.com is “the belief that the soul, upon death of the body, comes back to earth in another body or form.” Such claims lie outside the measurable parameters of science and are dubious. However, recent research is suggesting that perhaps some fears are indeed transferable across generations. How can this be?

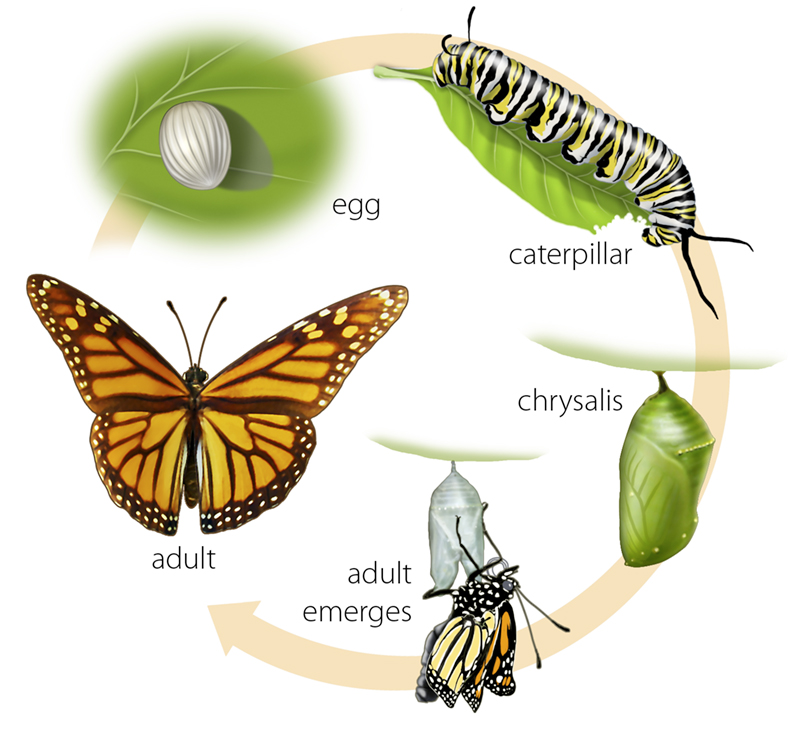

First, lets consider the life-cycle of a butterfly which commences as an egg laid by a mature butterfly. The egg hatches and a caterpillar (the larval stage) begins consumption of copious amounts of foliage (molting as he grows) in preparation for one of life’s most mysterious transitions. When the caterpillar is ready for its amazing metamorphosis, it cocoons itself into a chrysalis. During this phase the caterpillar essentially digests itself becoming a sack of ooze. It doesn’t transition from caterpillar into a butterfly by simply sprouting wings. Nope, it breaks down into a primordial soup and starts a remod from component cells called imaginal discs. These stem cells of sorts, comprised of just a small number of organized cells, ultimately reconfigure the sack of melted ooze into a fully functional butterfly. Although the imaginal discs have their beginnings in the egg stage, they remain essentially invisible but preparatory for the butterfly stage throughout the larval stage. They jump into rigorous reconstruction mode while in the chrysalis. This same process occurs in moths as well.

Life itself ceases for the caterpillar as it pupates in the chrysalis. It stops breathing, its heart stops beating: its muscles, skin and brain, legs, and antennae, all melt down, becoming liquid fodder for the resurrection. It’s not simply a transition – it’s a death and a rebirth.

So, you may be asking, how is this relevant? Let’s consider some amazing research by Martha Weiss, an Associate Professor in the Department of Biology at Georgetown University. Her research focuses on evolutionary ecology, plant-animal interactions, butterfly and wasp learning, and caterpillar behavior. One of her studies looked at whether learning during the caterpillar stage would make it across the pupal stage and be evidenced by the moth, despite the death and liquefication of the entire caterpillar. Such maintenance of memory was largely considered impossible. In her study, Dr. Weiss exposed caterpillars to a clearly distinguishable, but neutral odor, and then she paired the odor with a mild electric shock. Pretty quickly, after many repeated pairings, the caterpillars developed an aversion and a subsequent escape behavior, associated with the odor. They came to fear it.

Following the pairing sessions and demonstration of learning, the caterpillars pupated. Just over one month later, as mature moths, when exposed to the conditioned odor, the moths demonstrated a strong aversion to what would normally be a neutral stimuli. In this study there were also subjects that constituted the control group. The control moths were, when in the caterpillar stage, exposed to the odor but were not shocked. They never exhibited a definitive aversion to the odor (as caterpillars or moths). The caterpillars that were shocked, when presented with the odor, sustained the aversion even after pupating. The memory made it through the metamorphosis even though the caterpillar had died and the brain turned to goo in the meantime.

This is remarkable – and suggests that memories are capable of being sustained across the death of the caterpillar and the rebirth (probably as a result of the data sustained in the imaginal disks). As amazing as this is, such memories were not transmitted from adult moths through to the egg and onto subsequent generations of caterpillars. So memories can transcend metamorphosis, but is there any evidence of the capacity to sustain memories across generational lines like that implied by the Indigo Girls?

Researchers Brian Dias and Kerry Ressler from Emory University School of Medicine, in Atlanta used a similar research design with mice, whereby adult mice were trained to have an aversive response to the aroma of cherry blossoms. They repeatedly paired this particular odor with electrical shocks and the mice subsequently learned, through classical conditioning, to fear the conditioned odor. Unlike moths, mice procreate through intercourse, gestation, and give live birth to baby mice. There is no metamorphosis, although gestation is a pretty amazing process in its own right. Anyways, Dias and Ressler breed the mice who had developed the aversion and tested to determine whether their offspring also feared the conditioned stimuli (aroma of cherry blossom).

As it turns out, the offspring and their offspring evidenced an aversion to the cherry blossom odor despite never having been exposed to it or shocked. The fear appears to have been handed down across generations through a process called epigentics. Epigentic methylation results in changes in the DNA of the parent prior to conception that are then conferred to their offspring through sexual reproduction.

Granted this has not been scientifically evidenced in humans as yet, but the implications of these findings are staggering. This suggests that DNA is not immutable: that in fact, what happens to a parent prior to conception, can alter his or her DNA, and that those changes can be handed down across multiple generations. Epigentics is well established and this process is increasingly understood. But evidence of trans-generational fear responses have not been likewise so well substantiated. This ability had been seriously doubted. It is now conceivable that a survivor of a plane crash may later produce offspring who themselves have a subsequent fear of flying. This may explain human phobic responses to spiders, snakes, heights, and other irrational fears that were previously unexplainable.

This makes me think of my previous article titled Irrational Fear: It’s Just an Alief. In that article I wrote:

Philosopher Tamar Gendler has coined the word “alief” to describe this cognitive phenomenon. She fashioned the word around the word “belief,” which is a conscious manifestation of how we suppose things to be. An alief is a deep and powerful feeling of sorts that can and does play an important role in decision-making, but it is not based in reason or evidence. Beliefs can be more susceptible to such rational forces. But aliefs defy reason and exert powerful influence despite one’s attempts to rationally dispel them. This voice is intuitive and its origins are outside your awareness. They typically appear in an attempt to facilitate self-preservation.

To call such fears an Alief just gives it a name. The underpinnings of such fears have been vague and speculative. The findings of Dias and Ressler provide a testable hypothesis for such phenomena. And now, when I stand at an intimidating precipice, I can speculate that my fear stems from an incident experienced by unfortunate kin rather than from random bad karma.

References:

1. Blackiston DJ, Silva Casey E, Weiss MR (2008) Retention of Memory through Metamorphosis: Can a Moth Remember What It Learned As a Caterpillar? PLoS ONE 3(3): e1736. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001736

2. Dias BG, Ressler KJ (2014). Parental olfactory experience influences behavior and neural structure in subsequent generations. Nature Neuroscience (17):89–96.

3. Jabr F. (2012) How does a caterpillar turn into a butterfly? Scientific American

4. Radio Lab (2014) Black Box.

Has Epigentic methylation that results in changes in the DNA of an rodent animal parent prior to conception that are then conferred to their offspring through sexual reproduction been studied in humans since this article was written?

Sorry Robert for the delay in response. I really do not know the answer to your question. In the form tested in moths and mice, it would be an impossible study to replicate in humans due to ethical constraints. The genetic studies literature is above my head, but there may be a means of studying epigentic methylation in ways that get at whether it is indeed possible to transmit fear through the human germ line. The mouse study seems to suggest that it is possible (genes are genes). I suppose that it is possible to study across-generational fears in identical twins (reared by different parents and in unaffiliated households), but OMG, there are so many variables to control for. If you come across anything please share.