“I saw it with my own two eyes!” Does this argument suffice? As it turns out – “NO!” that’s not quite good enough. Seeing should not necessarily conclude in believing. Need proof? Play the video below.

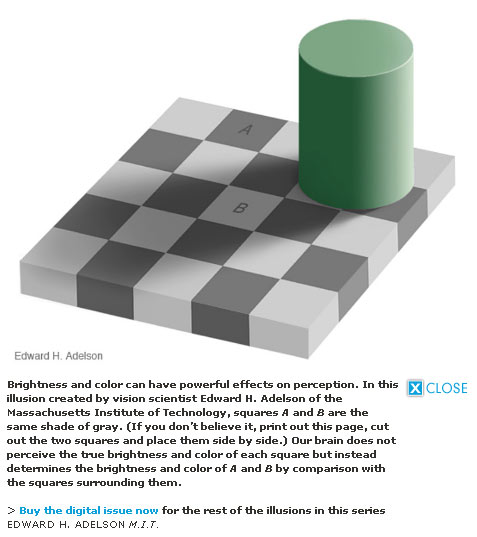

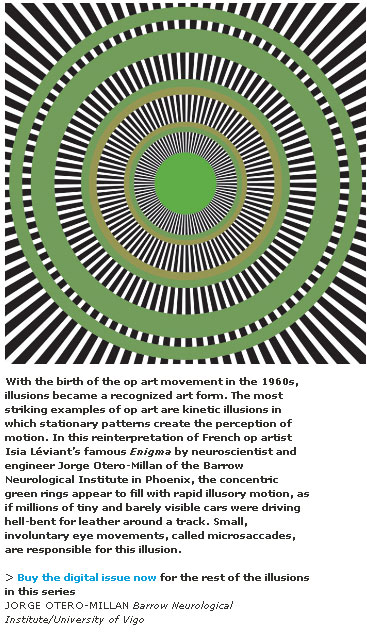

As should be evident as a result of this video, what we perceive, can’t necessarily be fully trusted. Our brains complete patterns, fill in missing data, interpret, and make sense of chaos in ways that do not necessarily coincide with reality. Need more proof? Check these out.

Convinced? The software in our brains is responsible for these phenomena. And this software was coded through progressive evolutionary steps that conferred survival benefits to those with such capabilities. Just as pareidolia confers as survival advantage to those that assign agency to things that go bump in the night, there are survival advantages offered to those that evidence the adaptations that are responsible for these errors.

So really, you can’t trust what you see. Check out the following video for further implications.

Many of you are likely surprised by what you missed. We tend to see what we are looking for and we may miss other important pieces of information. The implications of this video seriously challenge the value of eye witness testimony.

To add insult to injury you have to know that even our memory is vulnerable. Memory is a reconstructive process not a reproductive one.2 During memory retrieval we piece together fragments of information, however, due to our own biases and expectations, errors creep in.2 Most often these errors are minimal, so regardless of these small deviations from reality, our memories are usually pretty reliable. Sometimes however, too many errors are inserted and our memory becomes unreliable.2 In extreme cases, our memories can be completely false2 (even though we are convinced of their accuracy). This confabulation as it is called, is most often unintentional and can spontaneously occur as a result of the power of suggestion (e.g., leading questions or exposure to a manipulated photograph).2 Frontal lobe damage (due to a tumor or traumatic brain injury) is known to make one more vulnerable to such errors.2

Even when our brain is functioning properly, we are susceptible to such departures from reality. We are more vulnerable to illusions and hallucinations, be they hypnagogic or otherwise, when we are ill (e.g., have a high fever, are sleep deprived, oxygen deprived, or have neurotransmitter imbalances). All of us are likely to experience at least one if not many illusions or hallucinations throughout our lifetime. In most cases the occurrence is perfectly normal, simply an acute neurological misfiring. Regardless, many individuals experience religious conversions or become convinced of personal alien abductions as a result of these aberrant neurological phenomena.

We are most susceptible to these particular inaccuracies when we are ignorant of them. On the other hand, improved decisions are likely if we understand these mechanisms, as well as, the limitations of the brain’s capacity to process incoming sensory information. Bottom line – you can’t necessarily believe what you see. The same is true for your other senses as well – and these sensory experiences are tightly associated and integrated into long-term memory storage. When you consider the vulnerabilities of our memory, it leaves one wondering to what degree we reside within reality.

For the most part, our perceptions of the world are real. If you think about it, were it otherwise we would be at a survival disadvantage. The errors in perception we experience are in part a result of the rapid cognitions we make in our adaptive unconscious (intuitive brain) so that we can quickly process and successfully react to our environment. For the most part it works very well. But sometimes we experience aberrations, and it is important that we understand the workings of these cognitive missteps. This awareness absolutely necessitates skepticism. Be careful what you believe!

References:

1. 169 Best Illusions–A Sampling, Scientific American: Mind & Brain. May 10, 2010

http://www.scientificamerican.com/slideshow.cfm?id=169-best-illusions&photo_id=82E73209-C951-CBB7-7CD7B53D7346132B

2. Anatomy of a false memory. Posted on: June 13, 2008 6:25 PM, by Mo

http://scienceblogs.com/neurophilosophy/2008/06/anatomy_of_a_false_memory.php

3. Simons, Daniel J., 1999. Selective Attention Test. Visual Cognitions Lab, University of Illinois. http://viscog.beckman.illinois.edu/flashmovie/15.php

4. Sugihara, Koukichi 2010. Impossible motion: magnet-like slopes. Meiji Institute for Advanced Study of Mathematical Sciences, Japan. http://illusioncontest.neuralcorrelate.com/2010/impossible-motion-magnet-like-slopes/

Pingback:Tweets that mention You Can’t Trust What You See · How Do You Think? -- Topsy.com

Gerald,

Such a coincidence: I was planning to make my topic today the differences between perception and reality. Thanks for an informative post.